SOIL / GUT / BRAIN - Part 3

森林浴, 森林

Forest bathing, a concept that originated in Japan but is now backed by several governments around the world.

Shinrin-yoku

Japanese: 森林浴, 森林 shinrin, “forest” + 浴 yoku, “bath, bathing”

Covering two-thirds of its land area, Japan boasts extensive forests, lush greenery, and a diverse array of trees. Within Japan lies the Hokkaido region, considered the country's last great wilderness, and the Japanese Alps, characterised by extensive mountain ranges and dense pine forests. The term "shinrin-yoku'' was coined in 1982 by Tomohide Akiyama, the director of the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Following a series of studies conducted in Japan during the 1980s, forest bathing emerged as a recognized and effective therapeutic method.

Akiyama, informed by these studies and the health benefits associated with compounds like phytoncides and essential oils emitted by certain trees and plants, formally introduced shinrin-yoku as a practice. He actively promoted its advantages to the Japanese public and established guidelines for its implementation.

The development of shinrin-yoku was a response to the growing urbanisation and technological advancements in Japan. It aimed to encourage the Japanese population to reconnect with nature locally and serve as a means of preserving the nation's forests. The rationale was that by experiencing therapeutic solace in the forests, individuals would be motivated to actively contribute to their conservation.

The practice is now adopted in other countries and a few countries of note have done this with government support.

South Korea - Developed their inaugural therapeutic forest, Saneum National Recreational Forest, by The Korea Forest Service in 2009. Since then, the nation has expanded its therapeutic forest offerings, boasting 32 such forests by 2020. Over this time, the number of individuals engaging in forest bathing has notably risen, reaching approximately 1.5 million visitors by 2020.

USA - In the United States, the U.S. Forest Service has introduced forest therapy, facilitated by certified guides affiliated with the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy. These guides conduct immersive two-hour sessions in Puerto Rico's El Yunque Rainforest, guiding participants to experience the profound effects of forest therapy.

Finland - The Finnish Forest Association collaborates with the Finnish Forest Therapy Centre to champion forest therapy initiatives. These organised activities cater to forest visitors, emphasising well-being and holistic mind-body rejuvenation. A diverse range of participants, including groups, companies, and communities, partake in these forest therapy offerings.

There are many reasons why forest bathing is beneficial to us but for the scope of this article we’re considering how immersion in a complex ecosystem such as a forest can have a positive effect on our gut biome, research suggests that there are three inhaled factors that contribute being simply the inhalation of beneficial bacteria, negatively charged ions and the third being plant based essential oils, especially phytoncides.

Inhaled bacteria.

You might be wondering how breathing bacteria can end up in the gut? The nasal cavity and mouth are warm moist environments that have their own biome. These spaces collect and filter bacteria and viruses from the air we breathe and the mouth biome is the first step in the chain that leads to the gut biome, breathing and eating are using the same initial passageways.

Every day we humans each inhale up to 1500 litres of air and the air we breathe is far from sterile. Microorganisms comprising of bacteria, virus and fungi in the air are very very small, 1000x smaller than 1mm, these tiny single cells are very much alive but do not come together to form complex organisms or grow into anything more than a single cell, being so tiny they can either travel by being simply airborne on their own or can be carried on tiny particles of dust, the concentration of these in the air is referred to as a ‘bioaerosol.’

It's no surprise that lowland damp and temperate complex ecosystems provide a greater range and complexity of bioaerosol, as temperature and humidity decrease so does the abundance of microbes in the air but what is essential for microbial complexity is the complexity of the ecosystem they reside in.

Diagram showing the different airflow of mouth versus nasal breathing

Mouths are for eating and noses are for breathing

As a final note in this section it’s important to address not just where we breathe but how we breathe.

Our bodies evolved to breathe through our noses but many people primarily breathe through the mouth causing a wide range of health problems and the reason is simple, most people have nasal congestion.

The spaces we live in are unnatural environments, we breathe heated or air conditioned air that has humidity levels that are different from the air outside, we breathe a huge amount of industrial chemicals in our homes and outside, everything from transportation to cleaning products and manufactured goods creating allergies, infection and inflammation restricting the airflow through the nasal passage.

Another cause of mouth breathing is either a lack of or too short a period of breastfeeding, when an infant is feeding from the breast it learns to breathe properly through the nose, these patterns learned early can be set for life, for better or worse.

So why is mouth breathing a problem and how does it affect our biome?

To stay on track we will consider nasal versus mouth breathing in the context of the gut biome, there are many books and articles written about the myriad of benefits on other aspects of health.

The mouth cavity contains about 23% of all of the microbial density in the body and the gut contains 35% and the mouth is of course the gateway to the gut. When we mouth breathe we suck in everything, pathogens as well as beneficial bacteria but breathing through the mouth creates a drier environment creating a dysbiosis allowing bacteria that we don’t want to not just proliferate but then make it into the gut. Mouth breathing can

When we breathe through the nose we have a much more complex filtration system that is suitably moist and essentially the right environment for a healthy biome.

Shinrin-yoku

In part 2 of our investigation into gut health we looked at how we can improve the composition and complexity of our gut biome by consuming pre and probiotics but there is growing evidence that we can improve our biome through simply spending time in nature.

We know that spending time in nature can improve our stress levels as well as our general health and wellbeing but the mechanisms by which simply being in this environment cause these improvements are only just starting to be understood.

Apart from the sounds and sights of nature having a calming effect on our mind there’s research to suggest that one reason our health improves with time in nature is simply that we get exposed to a greater diversity of microorganisms that create ‘feel good’ chemicals and hormones such as serotonin in our gut which are in turn transported to the brain

Bacteria can enter our bodies through the obvious route of ingestion but we can also absorb them through our skin and mucous membranes mean that simply touching and breathing can introduce new bacteria to our biome.

You might remember earlier on we said that our gut is not really ‘inside us’ any more than our skin is, it is open to the outside world and shares a biome with the environment we’re in, meaning we benefit greatly from being in an environment with a rich diverse microbiome.

Activities in natural settings, like gardening, hiking, or playing in the dirt, can lead to direct microbial transfer from the environment to your skin and, indirectly, to your gut. These new microbes can potentially colonise your gastrointestinal tract and enhance diversity. Another factor that contributes to the positive effects of spending more time in nature is simply a reduced exposure to disinfectants, when we’re outside in nature we simply have less exposure to harsh disinfectants and antimicrobial agents commonly found in indoor environments. These substances can suppress the diversity of your gut microbiome by killing off various microorganisms both harmful and beneficial ones.

Phytoncides & essential oils

The third benefit of shinrin-yoku we will discuss is the benefit to humans of inhaling plant based defence chemicals.

It might seem counterintuitive that these substances that plants use to protect themselves by essentially poisoning their attackers can be good for us but these defence chemicals provide us with incredible benefits as they also protect us.

Phytoncides, originating from the Greek "phyton" meaning plant and the Latin "caedo" meaning to kill, are natural substances emitted by plants for communication and defence. They release these compounds into the air as a defence mechanism against unwanted fungi, viruses, and bacteria. Coined by Russian scientist Boris Tokin from Leningrad University in 1928, this term refers to specific plant emissions that deter various microorganisms. For instance, coniferous trees like pine and spruce produce alpha-pinene and other terpenoids as part of their defence mechanism.

Breathing in forest air exposes individuals to these terpenes, which assist the body in combating diseases. Terpenes constitute the primary components of forest air and have garnered attention in medicine due to their advantageous effects. The anti-inflammatory properties of terpenes offer relief in skin, ear, joint, and bronchial inflammatory conditions while alleviating lung irritation caused by cigarette smoke.

Moreover, research has validated the protective impact of terpenes against liver, breast, pancreas, and intestinal cancers. To maximise the benefits of forest air, morning visits are recommended as this is when the concentration of phytoncides in the air is typically at its peak.

Essential oils - Terpenes encompass essential oils, which serve as plant metabolites possessing anti-inflammatory and biocidal characteristics. Demonstrating efficacy against streptococci and staphylococci, essential oils are recognized for their antiviral attributes—like cedar, juniper, and sage oils—as well as their antifungal and anti-inflammatory properties. Inhalation of these oils assists in respiratory-related conditions, while direct exposure to their advantageous properties aids in addressing skin ailments.

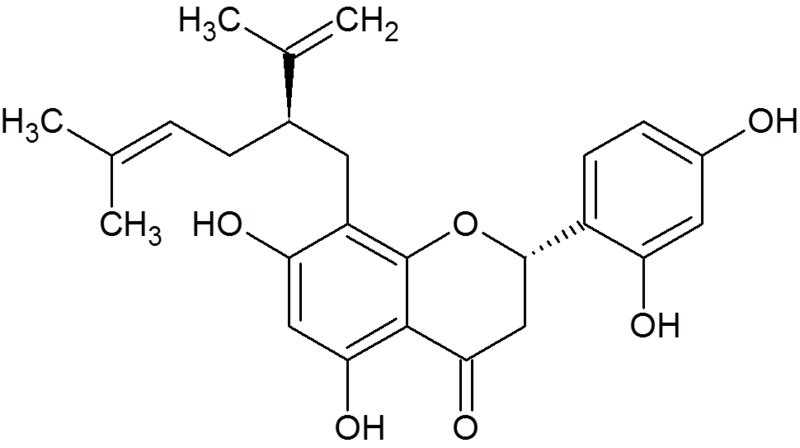

Sophoraflavanone G - A phytoncide of note!

Sophoraflavanone is a volatile phytoncide emitted by Sophora genus members into the air, soil, and groundwater, has garnered attention amidst escalating rates of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Scientific endeavors have centered on uncovering naturally occurring or genetically modified compounds capable of combating these perilous and occasionally fatal bacteria. Notably, Sophoraflavanone G's role as a phytoncide has revealed its ability to influence the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and augment the efficacy of existing antibiotics.

Negative ions

Ions are invisible charged particles in the air – either molecules or atoms, which bear an electric charge. Some particles are positively charged and some are negatively charged. To put it simply, positive ions are molecules that have lost one or more electrons whereas negative ions are actually oxygen atoms with extra-negatively-charged electrons. Negative ions are abundant in nature, especially around waterfalls, on the ocean surf, at the beach and widespread in mountains and forests. These charged particles can reduce inflammation in the human body as well as changing the charge of particulate matter that the body would otherwise have to filter from the air. Some studies have shown that breathing negative ions promotes energy production as well as acting as antioxidants and even lowering blood pressure. These positive health benefits directly affect the function of our microbiome in a synergistic manner.

In summary.

Our corporeal existence intertwines profoundly with the natural order; we are an embodiment of nature, seamlessly integrated without demarcation. These vessels we inhabit transiently hold elemental compositions, embracing a diverse mosaic of life forms in an eternal dance of birth and demise. Sensing and responding to environmental shifts, our beings engage in an unceasing exchange of information within an indivisible world.

The evolution of contemporary lifestyles has disrupted this harmony, fostering dysbiosis that restricts microbial information exchange with bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms. While dubbed as theory, the 'germ theory' substantiates the ability of viruses and bacteria to instigate human diseases. However, our pursuit of cleanliness comes at a price, impeding the ingress of beneficial microorganisms.

Remedying our biome's functionality lies within straightforward dietary approaches—embracing pro and prebiotic foods and incorporating locally sourced seasonal fare from intricate natural ecosystems. These measures transcend mere alignment with nature; they assimilate our existence into the fabric of the natural realm, delivering substantial benefits by mere proximity to natural settings.

Yet, the pivotal aspect in reclaiming our inherent robust health is safeguarding and rejuvenating the natural world that sustains us. Our agricultural systems endure their own state of dysbiosis, a consequence of a century of reductionist chemical farming practices.

Humanity possesses the agency to elect the environment in which we are an integral fragment. We hold the potential to be agents of restoration, nurturing nature's revival. As a pivotal keystone species, we can bestow vitality upon existence beyond what is achievable without our conscientious involvement. In this convergence, our thriving becomes imminent.

To discover our genuine essence, immerse oneself in the most pristine natural surroundings and breathe deeply through the nasal passage. Perhaps, one day, these sanctuaries shall be the bedrock of our agricultural sustenance...