Biohacking winter - Part 2

Part 2 - Eating for the season

In part 1 we considered how the comforts of modern life, once better understood, could be modified or hacked to be more in line with our innate biology, simply because technology changes much more quickly than biology. Evolutionary changes at the hormonal level, influenced by factors like climate, altitude, or other environmental factors, often involve multiple genetic changes and can take many many generations over hundreds if not thousands of years to become prevalent across a population. This means that as modern humans living in a world of global trade and creature comforts we’re sometimes at odds with our how our bodies respond at a genetic and hormonal level.

However, a little understanding of what out innate biology is can help us to navigate this to have the best of both worlds, to be able to enjoy the fruits of our technological world, global trade and full access to pretty much whatever foods we desire as well as lighting, heating and shelter without confusing our biological systems.

Living in a latitude that has seasons creates a much more complex biology than equatorial life where temperature, light and abundance varies very little year round. Over many many thousands of years our bodies have adapted to not just endure but to thrive in almost every climatic zone our incredible planet offers, humans have lived everywhere except the poles and understanding not just your genetic heritage but how epigenetics react to your latitude are essential for us to thrive in this modern world that is more homogenised

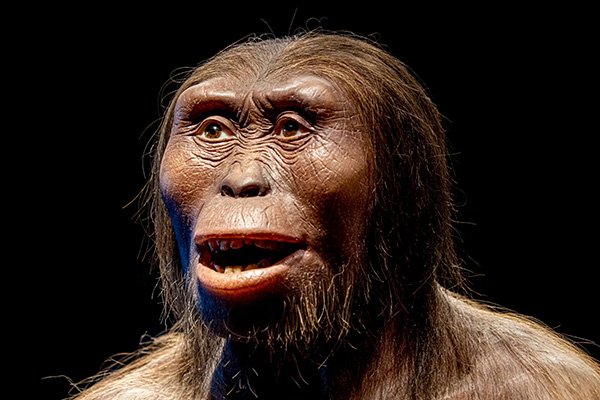

Computer imaging of Lucy, a 3.2-million-year-old hominin, whose incomplete skeleton was found in 1974

Let’s go back in time again…

Human life started where it was easiest, central Africa. This is because at that time the area of the world offered the greatest abundance of both plants and animals with very little seasonality meaning whatever was eaten was equally available year round.

The oldest known human-like fossils, such as those of Australopithecus afarensis ("Lucy") dating back around 3.2 million years, were discovered in Ethiopia, East Africa. Australopithecus afarensis had a unique combination of ape-like and human-like features. They were bipedal, meaning they walked on two legs, as evidenced by the structure of their leg and pelvis bones. However, their arms and certain skeletal features, like their small brains and projecting faces, were more similar to apes. Australopithecus afarensis likely lived in woodland or savanna environments. They were omnivorous, consuming a diet that included fruits, leaves, seeds, and possibly some meat scavenged from carcasses or obtained through hunting.

At the equator, seasons differ from those experienced in other latitudes. The primary annual difference lies in precipitation variations rather than significant temperature changes, resulting in nearly perfect 12-hour cycles of darkness and light every day. This consistent environment made things simpler from an evolutionary hormonal standpoint. The availability of the same food year-round and a consistent diurnal hormonal response to temperature and light, without seasonal fluctuations, streamlined the evolutionary process.

As early humans moved North and South they had to adapt.

Köppen climate categories

A current and updated version of the Köppen climactic zones which would have been digffernet in the time of ‘Lucy’

In 1884 climatologist Wladimir Köppen developed the Köppen System for classification of climatic zones and it is still widely used today.

The main Köppen climate categories are based on average monthly temperatures, precipitation, and the seasonal distribution of temperature and precipitation. Here are some of the primary classifications:

Global percentages of land area in Köppen climate categories

Tropical Climates (Group A): These regions generally have high temperatures throughout the year, with average temperatures above 18°C (64.4°F). They are further subdivided based on precipitation patterns:

Af: Tropical rainforest climates with abundant rainfall throughout the year.

Am: Tropical monsoon climates characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons.

Dry Climates (Group B): These areas experience limited precipitation, resulting in arid or semi-arid conditions.

BWh: Hot desert climates with high temperatures and very low rainfall.

BWk: Cold desert climates, generally with less extreme temperatures but still very low precipitation.

Temperate Climates (Group C): These regions have distinct seasons and moderate temperatures.

Cfa/Cfb: Humid subtropical climates with hot, humid summers and mild winters (Cfa) or no dry season (Cfb).

Csa/Csb: Mediterranean climates with hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters (Csa) or no dry season (Csb).

Continental Climates (Group D): These areas have more extreme temperature variations between seasons.

Dfa/Dfb: Humid continental climates with hot summers and cold winters (Dfa) or no dry season (Dfb).

Dsa/Dsb: Dry continental climates with hot summers and cold winters (Dsa) or no dry season (Dsb).

Polar Climates (Group E): These regions have extremely cold temperatures and limited vegetation.

ET: Tundra climates with very cold winters and short, cool summers.

EF: Ice cap climates with year-round freezing temperatures and little precipitation.

The United Kingdom falls primarily under the Köppen climate classification of Cfb, which represents a temperate maritime climate. The UK's maritime climate is influenced by the surrounding ocean, particularly the North Atlantic Current and the Gulf Stream, which moderate temperatures and contribute to the relatively mild winters and cool summers. Precipitation is distributed fairly evenly throughout the year, despite how it appears to us sometimes!

This zone dictates what natively grows here and pre-agriculture that means a summer that includes a few fruits and and autumn with berries but almost none of the vegetables and grains we that currently make up much of our diet are native and indigenous.

It's a challenge to identify truly native vegetables in the UK. Before agriculture, options included seaweed—remarkably all edible from the surrounding waters—and samphire, along with a few fungi. Closest to native would be plants like sorrel, carrots, and parsnips, which originated from wild ancestors but were selectively cultivated into their familiar forms.

Virtually every vegetable in a typical British kitchen is either imported or descended from imported varieties. So, what sustained people before invasions, imports, and cross-breeding filled our modern supermarket shelves? The answer lies predominantly in meat.

Meat, whether from land or sea, was consistently available. Our distant ancestors likely relied proportionately more on protein and fats than the average person does today. However, a significant difference was their limited access to sugars, available only briefly during certain times of the year.

Only the fattest survive!

As early humans moved away from the equatorial regions plant based foods became seasonal meaning there periods of plenty and periods of scarcity, the concept of feast and famine, and this became more and more extreme with distance from the tropics.

The success of humans being able to live in many different zones and to be able to travel was largely part to being very good at storing extra calories, and in tougher times when food was scarce, fat became the survival hero. Unfortunately, this legacy hasn't faded in our era of abundance. Our ancestors who passed on the most genetic information were likely those who easily gained weight. So, in a way, your distant lineage played a part in this. In extreme times only the fat survived as early humans moved north meaning this genetic trait became more pronounced.

Before mastering the art of cultivating, preserving, and storing food, early humans in regions like ours at 51.5 degrees north made do with what was available. In these latitudes, seasonal changes meant limited availability of sugars. Native fruits and vegetables were scarce from late autumn to late spring.

A bowl of butter or a plate of cookies, which one could you binge on?

Summer, however, was a feast. Trees bore sweet fruits, berries were plentiful, and starchy roots and tubers could be unearthed. Our ancestors would have indulged, knowing that fat storage was crucial for surviving the potentially harsh winters, in summer they gorged and got fat!

Our hunger levels are influenced by hormones like leptin and ghrelin. Ghrelin revs up appetite, while leptin taps the brakes. An odd evolutionary quirk is that consuming fructose or fruit sugars can cause leptin resistance. In simple terms, eating lots of fruit disrupts the signal telling us to slow down or stop eating. Many scientists view this as a vital evolutionary adaptation for our ancestors.

When we consume sugars, or more precisely carbohydrates, our bodies respond by releasing insulin in response to the rising glucose levels in our blood. Insulin aids in regulating blood glucose by ushering it into cells for energy production. In an insulin-sensitive state, this feedback loop ensures the right amount of insulin is produced to manage blood sugar levels. Yet, as with many things, excessive stimulation leads to issues.

Continuous activation of the insulin mechanism results in what's known as insulin resistance. This state accelerates the storage of excess sugars in fat cells once the muscles are saturated. While insulin’s immediate task is distribution, in evolutionary terms, it equates to survival—specifically, survival of the fattest.

For early human ancestors in northern Europe, access to sugary fruits was limited mainly to summer, when days were longer, often leading to reduced sleep. Moreover, this season brought elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

Summer is perfect to get fat

In Summer we have short daylight hours meaning our ancestors slept less, had more light stimulation leading to greater levels of the so called stress hormone cortisol and a short window of access to carbohydrates, these conditions are metabolically perfect for storing fat.

Initially, fat gets stored around critical organs for protection, the kidneys, heart, lungs, and digestive system all get a good cushion long before it becomes visible on the belly. Once these vital parts are shielded, fat starts accumulating in the familiar areas of the belly and torso. This additional layer serves as insulation against the impending cold months, these more visible fat stores are a different type of fat and are more eaily accessed by the body, this subcutaneous fat is essentially the human body’s version of a rechargeable battery and it is very very efficient.

The body’s preferred fuel source is carbohydrate, it is easily metabolised into energy through a relatively simple pathway giving quick access to energy but not much can be stored by the human body. Carbohydrate storage on the body is in the form of Glycogen which is a multibranched polysaccharide of glucose meaning it is simply a chain of glucose mollecules. Glycogen storage capacity in man is approximately 15 g/kg body weight and can accommodate a gain of approximately 500 g before net lipid synthesis contributes to increasing body fat mass or recharging the battery if you like.

In a review of multiple fasting studies, researchers found that it takes between 18 and 24 hours to deplete glycogen stores and more than 2 days after that for the body to shift into ketosis which means that all of the ‘sugar’ is gone and the body has shifted to burning its own fat as a fuel source.

In our modern privileged world we no longer experience periods of fasting that are not voluntary but our ancestors would have spent a lot of time without food, relying on their ‘batteries’ of stored body fat but there was another metabolic process that happens when we do not have access to foods and that is of a protein scavenging called autophagy.

Autophagy and ketosis - ancestral survival metabolic processes that have huge health benefits.

Mechanism of cellular authophagy, Credit: iStock/Dr_Microbe

Above we mentioned that our food can be categorised by three macronutrients being carbohydrates, fats and proteins, out of those three two are essential, without them we die, the third we can survive without and that one is carbohydrate.

Total absence of protein and fats leads eventually to death, we have the ability to store carbohydrate as fats for later usage but we don’t quite have same ability to store protein so in times of scarcity such as fasting or famine another process takes over called autophagy.

Taken from the Greek autophagy literally means self eating and this process has profound health implications as the cells that are ‘eaten’ first are the ones we no longer need, just as when we’re in ketosis the body will burn the belly fat before the fats that are protecting the organs when there’s a lack of protein it serves as a cellular "clean-up" mechanism, clearing out accumulated waste, misfolded proteins, and potentially harmful cellular debris.

his clearance contributes to maintaining cellular cleanliness and reducing the risk of various diseases, including neurodegenerative conditions.

The old proteins are scavenged and reassembled before muscle catabolism occurs saving as much of the benefical structure of the body as long as possible. Our bodies really are utterly incredible in their ability to adapt!

Winter is a time for healing, renewal and getting lean!

We’ve described above how our bodies have through evolution, become adapted to the make the most of the excesses of both sugar and light in the summer to recharge the body’s battery and use the perfect metabolic processes to store this potential to see us through harder times in the winter but this time of winter was keeping us in balance and health, the scarcity meant we has periods of cleaning though autophagy and ketosis while cortisol levels were lower so were our insulin levels.

Diabetes is a serious public health problem, could it be caused by us not living within the rhythms of nature?

Another effect that periods of abstenece from carbohydrate offers us is an increase in insulin sensitivity. When the body is using fats or ketones as a fuel source much less insulin is being produced, this ‘rest’ allows the cells to become more sensitive to insulin in the future meaning that when carbohydrates are consumed again the correct amount of insulin is produced to rebalance blood sugar levels. When carbs and sugar are constantly consumed the system becomes tired, the body becomes much less sensitive, this is called insulin resistance and it means that too much insulin is produced for a given rise in blood sugar levels, this excessive amount of insulin causes blood sugar levels to fall quickly leading to an energy crash and moire sugar cravings creating a vicious circle that can cause the pancreas to eventually not be able to produce enough insulin and this can lead to type 2 diabetes as well as causing a whole host of other health problems. If you remember back to part 1 this effect is exacerbated by elevated cortisol levels from ‘bad’ lighting.

Insulin resistance causes elevated blood sugar levels and contributes to inflammation, oxidative stress, and damage to blood vessels, increasing the likelihood of atherosclerosis (plaque buildup in arteries), heart attacks, and strokes as well as causing weight gain and obesity, in short, many of our diseases of lifestyle are exactly that diseases caused by living in a perpetual summer without allowing our bodies to rebalance in the winter. It is estimated that 3.8 million people aged 16 years and over in England have diabetes (diagnosed and undiagnosed). This is equal to 8.6% of the population of which 90% are type 2 meaning that they are largely caused by lifestyle.

A note about ultra processed foods

In these last two articles we’ve scratched the surface of some of the incredibly complex interlinked systems that keep our incredible bodies in line with nature. The intricate loops and feedback mechanisms that control our satiety and storage, that keep us in balance in the seasons and give us the ability to not just endure an ever changing environment but to adapt and thrive with greater vitality than repeating the same patterns of nutrition and behaviors year round. Or bodies know when we need fats, sugars, proteins and salt as they become available throughout the seasons as different signals and reward centres are triggered. In nature most of the foods we eat contain mainly one or sometimes two macronutrients, fats and proteins exist in meats and sometimes in plants such as nuts and some seeds, however, there are some combinations that very rarely occur in nature and they send our brains into a tailspin and the food industry knows this all too well.

Eastern thought on seasonal eating

It’s worth considering two eastern traditions of eating for health, that of macrobiotic and ayurveda

Macrobiotic

Macrobiotic eating is a dietary approach that emphasises whole, natural foods and seeks to balance the yin and yang energies within the body. It originated from ancient Chinese philosophy and was further developed by Japanese philosopher George Ohsawa in the 20th century.

A strong theme in the macrobiotic ethos is that of seasonality, seasonality linked to environment meaning a macrobiotic diet in the tropics isn’t the same as in Scandinavia. In the macrobiotic philosophy, the choice of foods during different seasons is believed to impact the body's internal balance of yin and yang energies. For instance, consuming an abundance of juicy tropical fruits during the winter in a temperate climate, like the UK, is thought to introduce cooling properties to the body, leaning it excessively towards the yin spectrum.

Conversely, favouring locally available root vegetables, squash, cabbages, and greens—typical winter produce in temperate zones—is believed to promote a more balanced equilibrium between yin and yang energies within the body. This balance is presumed to positively affect overall health and vitality according to macrobiotic principles.

While tropical fruits indeed offer valuable nutrients, their cooling and hydrating properties might not be as suitable for the body's needs in a colder climate. The emphasis on root vegetables and winter greens aligns with the body's potential requirements for warmth and sustenance during winter, supporting metabolic processes and helping to maintain body temperature.

Ayurveda

Ayurveda is an Indian system of health and wellness which revolves around the concept of three fundamental energies or doshas—Vata (air and space), Pitta (fire and water), and Kapha (earth and water). Each individual is believed to have a unique combination of these doshas, influencing their physical, mental, and emotional characteristics and health is said to come from balancing these energies

In Ayurveda, foods are categorised based on their tastes, qualities, and effects on the doshas. Each food is believed to possess its own inherent qualities that can influence the balance of the doshas in the body.

Within the ayurvedic system certain foods are thought to counteract the cold and dampness we experience in the British winter, this manifests as the Kapha dosha which is characterized by the elements of earth and water, representing qualities that are heavy, cold, slow, stable, oily, smooth, and dense.

To balance the Kapha dosha in Ayurveda, incorporating foods with opposing qualities—such as warm, light, and stimulating—is recommended. These foods help counteract the heavy, cold, and dense qualities of Kapha. Here are some dietary suggestions:

Spices: Include warming spices like ginger, black pepper, cinnamon, cloves, mustard seeds, and turmeric. These spices help stimulate digestion and provide warmth.

Light and Dry Foods: Opt for light and dry foods to counteract the heaviness of Kapha. These include grains like quinoa, barley, millet, and couscous.

Vegetables: Choose vegetables that are more pungent, bitter, and astringent in taste, such as leafy greens (spinach, kale), cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cauliflower), radishes, celery, onions, and garlic. These vegetables are lighter and help balance Kapha.

Legumes: Incorporate legumes like lentils, mung beans, adzuki beans, and chickpeas in moderate amounts. They are lighter than some other protein sources and can help balance Kapha when consumed in moderation.

Fruits: Favor fruits that are less sweet and juicy, such as apples, pears, berries, pomegranates, and apricots. Limit heavy and sweet fruits like bananas and mangoes.

Herbal Teas: Enjoy herbal teas with warming and stimulating properties, like ginger tea, cinnamon tea, tulsi tea (holy basil), or dandelion tea. These can help balance Kapha and improve digestion.

Healthy Fats: Incorporate moderate amounts of healthy fats like ghee (clarified butter), sesame oil, or olive oil. Avoid excessive consumption of heavy or oily foods.

Even though ayurveda and macrobiotics have distinct principles, origins, and frameworks they are remarkably similar in their advice for seasonal eating as both frameworks are seeking balance and that comes from understanding what is available where you are at a particular time of year.

So what should we be eating in winter in the UK?

At this early stage of winter (December) there is a surprising amount of produce available to us as late crops are still coming though and the last of the tree fruits are just about available due to their keeping qualities.

Root vegetables

Right now is peak season for carrots, parsnips, swedes, turnips, potatoes, beetroot, celeriac and jerusalem artichokes. These veg are hugely versatile and can be roasted, baked, boiled or mashed and welcome strong warming spices and seasonings. Root veg are rich in nutrients that support our health at this time of the year such as vitamin C, potassium, magnesium, and various B vitamins, equally importantly (see part 1) they are rich in various types of fibre, both soluble and insoluble.

Cruciferous vegetables are so named because of a cross like structure of leaves.

Brassicas

Brassicas, also known as cruciferous vegetables, encompass a wide range of plants and they are the nutrient powerhouses of the vegetable world. The name "cruciferous vegetables" comes from the botanical classification of these plants within the Brassicaceae family, formerly known as the Cruciferae family. The name "Cruciferae" is derived from the Latin word "crucifer," meaning "cross-bearing."

The term refers to the shape of the flowers of these plants, which have four petals arranged in the shape of a cross. This distinctive flower structure is a common characteristic among plants in this family, including broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, Brussels sprouts, kale, and others.

Compounds found in brassicas, including glucosinolates, sulforaphane, and indole-3-carbinol, have been studied for their potential to inhibit the development of certain cancers. These substances may help by blocking the growth of cancer cells and supporting detoxification processes in the body. These vegetables are also have anti-inflammatory properties and support heart health lowering blood cholesterol as well as being very low in calories, however, they require careful preparation, if you boil these veg and throw the water away you’re throwing away beneficial nutrients, however, especially in the winter, they should not be consumed raw. he can be lightly sauteed in some butter, ghee or even bone broth or stir fried hot and fast.

Onions and garlic

Now is a great time of year to add a little extra onions and garlic into you diet as both support immune function. Allicin, found in garlic, has antimicrobial properties and may help fight off colds and other infections also, these vegetables contain compounds that may have mild expectorant and decongestant properties.

Citrus fruits

This category might be considered the wild card in this list because these fruits do not grow in the UK unless indoors, however, they’re not from far away being mediterranean rather than tropical and they are in season at this time of year. Citrus offer great health benefits to us in the winter being relatively low in sugar but high in immune boosting vitamin C as well as flavonoids, such as hesperidin and naringenin, which have antioxidant properties. These compounds may help reduce inflammation, improve blood circulation, and support heart health.

Apples & pears

The humble apples and pears would historically have been eaten well into the winter as they store very well, however, looking at the Eastern traditions they could hasve a cooling effect on the body so if you’re prone to being excessively cold in the winter cook with these fruits to increase their warming effect

Although not native squashes and pumpkins offer us great nutrition for the winter months

Nuts

Chestnuts walnuts and hazelnuts are all in season in the UK, coming back to Ayurveda they are definitely recommended. Nuts are believed to enhance ojas, which is considered the essence of immunity, vitality, and overall health in Ayurveda. They are thought to nourish and strengthen the body when consumed in moderation, however, it’s important to eat the right ones for winter as for example almonds are often recommended for Vata and Pitta imbalances due to their grounding and cooling properties so should be avoided in the UK winter. On the other hand, cashews might be suggested in moderation for their warming nature. Hazelnuts are considered to be warming and some practitioners suggest that hazelnuts have a grounding quality, which might benefit individuals with a Vata imbalance. Grounding foods are thought to bring stability and help calm an overactive Vata dosha, these people would tend towards having dry skin and poor circulation and suffering from cold hands and feet.

Squashes and pumpkins

Another slightly wild card as strickly these are not native to the UK, however, they grow well here and fit in with our genetic code and seasonal requirements for eating. They originated in the Americas and were introduced to Europe after the exploration of the New World. Squashes, including various types like butternut squash, acorn squash, and others, along with pumpkins, are part of the Cucurbitaceae family. They were cultivated by indigenous cultures in the Americas for thousands of years before being introduced to Europe and other parts of the world by explorers and traders.

Some compounds found in cucurbitaceae, such as cucurbitacins and flavonoids, possess anti-inflammatory properties that may help reduce inflammation in the body and the high level;es of potassium help to regulate blood pressure. These vegetables should be enjoyed liberally throughout the winter and can be prepared in many ways from baking, steaming, roasting and mashing.

Game meat

Truly wild game meat is a very different food on so many levels from the industrially produced meats we see in a supermarket. Its is generally leaner, much more nutrient dense and higher in Omega-3 fatty acids before we even start on the ethical and environmental considerations. Much of the game in the uk is not truly wild as it is bred to be hunted but deer is an animal we must control regardless. The UK has two native species of deer being Red and Roe and several non-native but invasive species such as Sika and Muntjac (introduced from Asia by wealthy landowners) and Fallow deer introduced by the Normans around the 11th century. This is a much underused resource in the Uk with a lot of the venison produced being shipped abroad where it is more valued, if you want to truly connect with seasonal eating in the UK put venison back on the menu.

Air freight of out of season native produce should be avoided at all costs

Think mostly local in a global world

The intricate web of the global food supply chain is a marvel we'll explore more deeply in upcoming articles. While we don't suggest forgoing the pleasures of non-native foods—like rice or coconut—that add immense richness to our lives, a diet centered around local and seasonal produce offers not just vitality but also reduces the carbon footprint of our meals.

Yet, there's a group of produce we advocate limiting: non-seasonal air-freighted goods. These items, although possibly available, are out of season locally and are flown in from regions where seasons are inverted from ours. Until they're back in season in the UK, it's advisable to avoid them. When they do return, consider preservation methods like freezing, pickling, or dehydration if you can't do without them.

For instance, berries such as strawberries, raspberries, blueberries, and blackberries are flown in during the UK winter despite being locally grown in abundance during the summer months.

Similarly, green beans, usually harvested in the UK summer, might find their way here in winter from warmer climates.

Even salad greens, including lettuce varieties and spinach, commonly cultivated in the UK summer, are air-freighted when out of season.

While the UK boasts year-round greenhouse tomato production, certain specialty types might still be air-freighted in winter from countries with prolonged growing seasons.

Limiting reliance on these air-freighted non-seasonal goods in favor of local, seasonal alternatives not only promotes healthier eating but also aligns with sustainable food choices that benefit both our health and the planet.

Spiritual and physical health

The choice to consume local, seasonal foods extends beyond basic nutrition; it represents an alignment with a profound philosophical paradigm, deeply rooted in the natural rhythms and cycles of our environment, and the spiritual fulfilment they provide.

At its core, this approach embodies an age-old wisdom that respects the seasonal flux as a reflection of the ephemeral yet perpetual essence of life. By synchronising our dietary habits with the tempo of local harvests, we foster a harmonious relationship with the cyclical nature of the earth. This act is more than mere consumption—it is a ritual that celebrates the interdependence of all life forms and our symbiotic bond with the land.

This practice is a tribute to the land itself, acknowledging the inherent wisdom in its abundant produce. It's a deliberate acknowledgement that our food is not just physical sustenance but also a carrier of the narratives, energy, and essence of a particular locale.

From a biological perspective, this choice may subtly intertwine our genetics with the land. The distinct biochemical profiles of local flora, shaped by their seasonal cycles, might gently interact with our genetic makeup, echoing themes of adaptation and resilience. This interplay between nature and nurture could resonate with the intelligence embedded in the local soil.

Moreover, this philosophy extends beyond individual well-being to encompass collective environmental responsibility. It represents a commitment to sustainability and ecological preservation. Supporting local agriculture minimises our ecological footprint, fostering reduced carbon emissions and enhanced biodiversity. This approach positions us as stewards of the land, safeguarding its health for future generations.

In embracing local, seasonal foods, we engage in a journey that transcends conventional dietary choices. It becomes a philosophical and artistic exploration, elevating the act of eating into a sacred communion, nourishing both the soul and the planet. This spiritual practice is accessible through a simple, yet impactful choice: prioritising local, seasonal produce in our daily consumption.